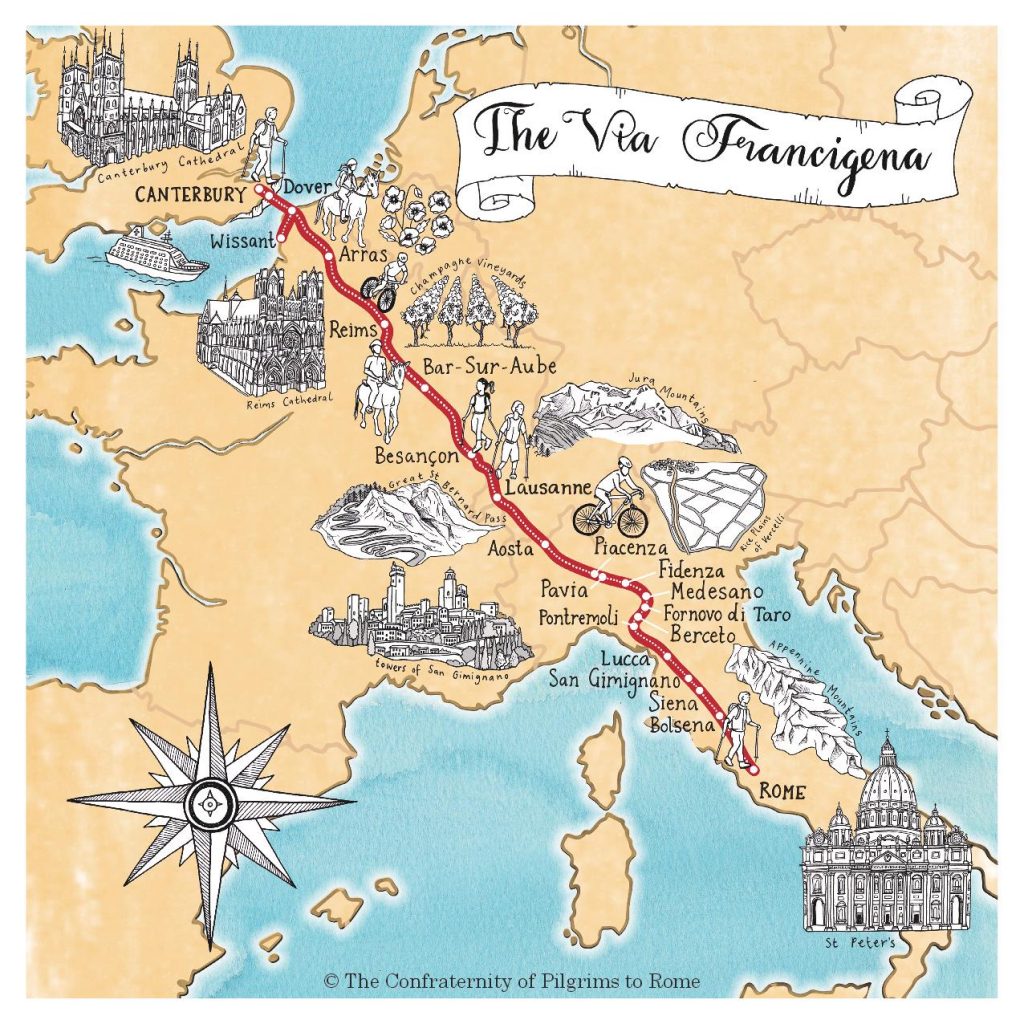

The Via Francigena, or ‘Frankish Road’, was the main road from Rome via the Great St Bernard Pass to territories of the Franks north of the Alps. The route then continued, crossing the Jura mountain range in northern France and ending in Canterbury, England.

In the century following the sack of Rome (in 410AD) by Alaric and his army of Goths, and disintegration of the Roman Empire, the Via Francigena was established through territory occupied by the Franks. It was a direct and secure route with regular overnight stopping places, often in fortified groups of houses (borgo). Many of these established during the reign of Theodoric (493–525AD) housed small religious communities, which provided accommodation for travellers.

What happened after the Franks?

After re-taking strongholds from the Franks and Ostrogoths in Northern Italy, the Byzantines were assisted by the Longobardi (or Lombards), who were invited to stabilise the recaptured areas. In 569AD the entire Lombard tribe crossed the Alps into Italy. They established a capital in Pavia, and maintained the Via Francigena as the main route to what became the Lombard Kingdom of Italy, extending to Benevento, south of Naples. The route and its infrastructure was developed, often through endowments to religious communities, particularly during the reign of the Lombard King Liutprand (713–742AD), a period of peace and prosperity.

How do we know the route of the early Via Francigena?

In 990AD Archbishop Sigeric of Canterbury travelled to Rome to receive his pallium (a woollen cloak of office) from the Pope. On his return journey he made a record of his route.

Was the Via Francigena a clearly defined road?

Where the route crossed a pass or river, or entered a town, there was usually a single route. In many places, however, the route fanned out, providing a range of options. Pack animals, flocks and herds were notorious for taking routes other than the hard stony main one, particularly if these offered opportunities for grazing. Other routes might evolve because they led via springs, shrines, chapels or hermitages, or places where travellers could obtain food and spend the night.

Ultimately, all roads led to Rome.

Was there a ‘season’ for travel on the Via Francigena each year?

The ‘season’ for travellers from north of the Alps depended on snow conditions, but usually the passes were open by early June and closed by late October. Many travellers would cross late and spend the winter in Italy. December to March tended to be quiet months on the Via Francigena, but during spring, summer and autumn, the winter trickle of travellers turned into a flood.

How far did people travel in a day?

Time taken on the route depended on hours of daylight. In winter travellers were confined to short stages (about 6–8 hours of travel). In summer, 12–14 hours was possible, although few could sustain this over long distances. The average day’s journey, allowing time to rest and find somewhere before dusk to eat and spend the night, was about 8 hours. Walking in mixed groups the average speed was about 2 miles in an hour.

How many people travelled the route each year?

At the peak period in a busy ‘Jubilee’ year, over 20,000 people a day were recorded passing through the gates of Siena. The average number of people travelling the route each day was probably closer to 2–3,000, on their way to Rome and back.

Perfectly preserved Siena

What was the economic impact of the Via Francigena?

‘The Main Road of Europe’ was a source of wealth to the areas through which it passed. Providing not just shelter, but food and drink for thousands of people each day, it created employment and an almost insatiable demand for local produce, as well as opportunities for stall-holders and traders in foodstuffs and livestock who came from far and wide. Many of the ancient ‘service’ trade and drove roads remain today.

What sort of people travelled the Via Francigena?

Those who met along the way would have ranged from pilgrims to merchants, farmers and drovers, teams of pack horses and mules carrying goods from all over Europe – whether wool from England, cloth from Flanders or ceramics from Deruta – masons on their way to sites of great cathedrals, artisans, students, clergy, the military, administrators, and entertainers. Some would have been on horses; most would have travelled on foot. The wealthy would have had an entourage with stewards sent ahead to prepare a suitable reception and accommodation along the route.

The walled, hilltop town of Monteriggioni

How did the Via Francigena cope with the stream of travellers?

The Via Francigena, like the Camino de Santiago and other busy routes, was highly organised. Communication up and down the route was good. Approximate numbers of travellers in transit each day were reported so that those further down the route could prepare and cater accordingly.

What was it like travelling down the Via Francigena in 1300, for example?

It is unlikely that you would have travelled alone! People tended to travel in groups of 20 or more. This was partly for safety in numbers against brigands, but also for companionship, and because groups could generally ensure better treatment along the way. Each group had its own leadership and dynamic.

Where the route passed through villages there were stalls selling food, and inns or taverns – often simple affairs such as a room or cellar with benches and barrels. Organisation of overnight accommodation was made easier because people travelled in groups. Those offering accommodation would position someone on the route each afternoon and travellers would look for a Canon, monk or innkeeper, depending on where they wanted to stay. Once capacity of one location had been filled, travellers were directed to another – and there was usually a gaggle of children to act as guides if the way was unclear.

Medieval inns were often crowded, rough and rowdy. The ‘better class’ of inn was relatively expensive, and a few had private rooms for those who could afford them. Most, however, had innkeepers not noted for their integrity, food that was poor quality, and crowded conditions with people sleeping three or four to a bed, with assorted vermin, whilst rubbing shoulders with thieves and murderers.

A band of pilgrims would choose a canonry or a monastery atwhich to stay. After arrival they would be greeted and fed at long tables with benches, or outside if the weather was fine. Feeding hundreds of people every evening required a large, well-organised staff. The census of 1200, for example, records 180 people living and working at just one canonry on the route, Pieve a Castello.

Pieve a Castello, one of the few remaining canonries on the Via Francigena – and now owned and operated by ATG.

Canonries and monasteries usually had dormitories for visitors, and also used the claustrum (courtyard or cloister), but the church itself was also an important resource. Churches had piles of straw mattresses ready for use each night. Many churches also had additional floor-levels, galleries and lofts, where people could sleep. Outside there were loggias, barns and lean-to shelters where people both ate and slept. Toilet facilities were well-organised.

Bed-time, after an evening service, was at dusk. Candles were not allowed in communal sleeping areas due to the risk of fire. Food for late-comers was set aside in a high alcove, out of reach of dogs. Bakers would work through the night. Dawn would be followed by another service and people would be given a piece of bread and meat or cheese for their journey.

They would make their offering of money to the monastery or canonry, and then the group would assemble and set off again. Travel was a well-organised, highly sociable activity with a strong sense of purpose, and enjoyed by millions of people every year.

What happened to the Via Francigena?

The Via Francigena survived successive changes of power and influence, conflicts and invasions for nearly 1,000 years. In 800AD Charlmagne travelled down the Via Francigena to be crowned Emperor in Rome. In the year 1000AD vast numbers of people streamed from all over Europe to Rome, and travel increased over successive centuries. After 1400, however, Florentine dominance led to the route being diverted via Florence. Meanwhile, the power of the Church had been permanently weakened and the fashion for pilgrimage declined. The old ‘Main Road of Europe’ that once thronged with millions of travellers each year, degenerated into farm and forest tracks. Overnight stopping places on the old route lost their raison d’etre, but a few, like San Gimignano and Pieve a Castello, have survived as part of a remarkable historic heritage.

Picturesque San Gimignano

Millennium celebrations in 2000 saw a revival of the Via Francigena – with modern-day ‘pilgrims’ enjoying savouring the discovery that the best way to see a country is – still – on foot.

Walk the Via Francigena with ATG Oxford

ATG offers the opportunity to walk the full 225 miles from Siena to Rome, in three consecutive Footloose sections:

Additional Footloose routes that follow the Via Frangicena:

Escorted tours that feature the Via Francigena:

The best way to see a country is on foot! For an overview of all dates and prices across our

The best way to see a country is on foot! For an overview of all dates and prices across our  2025/2026 Tours For an overview of 2025/2026 dates, click here Idyllically located in unspoilt countryside between Siena – ‘the best-preserved,

2025/2026 Tours For an overview of 2025/2026 dates, click here Idyllically located in unspoilt countryside between Siena – ‘the best-preserved,